Jaimie Johnston, head of global systems at Bryden Wood explains why hoarding IP won’t save construction (and what we need to do instead)

In 1956, Dr. Mervin J Kelly, an American physicist and engineer, enters a courtroom in New Jersey for the verdict in one of the most important antitrust cases in history.

Kelly is president of Bell Labs, the main provider of telecoms services in the US and his company is the subject of a long-standing lawsuit to break up the Bell System, which is (allegedly) monopolising the market.

The outcome of the trial is dramatic. Bell Labs is forced to license all its patents royalty free and is simultaneously barred from entering any industry other than telecommunications. So, almost 8,000 patents in a wide range of fields (1.3% of all the then current US patents) become freely available to anyone. The patents cover technologies created by the most innovative industrial laboratory in the world – the lab that invented the transistor, the solar cell, and the laser – and suddenly all their secrets were out. However, the innovation, competition and collaboration that followed the judgement changed the industry and then the world.

We now recognise that this very moment was the birth of Silicon Valley.

The case for open sourcing in design and construction is no less compelling. We know the industry can’t continue in its current form. We won’t meet the UK’s need for housing, education, healthcare and transport infrastructure by designing and building traditionally. Change is essential.

A new, open source solution

We can’t adopt a sophisticated digital design process while using Victorian construction methods. We can’t tack design for manufacture and assembly (DfMA) on to a traditional design approach.

Both the digital and physical processes must transform simultaneously, and both must be open source.

Fragmentation in the design to delivery process has created narrow but deep specialist roles – for instance the ‘architect’ may now comprise a concept architect, an executive architect, a façade architect and an interiors architect. Consequently, an asset’s design undergoes multiple handovers from concept to detail to fabrication, and so on. At every stage, design gets diluted and ‘value engineered’. Current procurement methods encourage everyone to limit their scope of work to well-defined and defensible pieces, and pass risk down the line. The result is a protectionist environment with little scope for innovation. When innovation does happen, it’s in small pockets and focused on one aspect of the process.

We think a number of things are needed to reverse this trend.

Firstly, a new, holistic, design process that simultaneously considers client values, design, procurement and assembly (on and off site). It needs to be technology-based and highly digital but that’s not all. It must be intrinsically linked to (and maximise the benefits of) DfMA.

Secondly, we must recast the sharing of knowledge, and create common solutions that everyone can unite behind and progress. This will only happen if we open source best practice for the collective good. The issue facing the industry is not a lack of potential work – UK government is investing £600 billion in the built environment over the next 10 years – it is our ability to deliver high performing assets with our current capabilities. Easy to say, harder to action. But at Bryden Wood we’ve begun by developing a number of open-source innovations.

Creative, technology-led design

The vision for BIM was to enable designers to use data from existing assets to make better informed decisions at the front end of the design process. However, because these tools get deployed once the concept design has already been developed, there is a missing link that would allow a truly data driven design process.

Bryden Wood has created and launched three web-based, free, algorithmic tools to allow the digital design process to start much earlier – and go much faster – before feeding into existing BIM workflows. The result is a complete digital process from design to delivery.

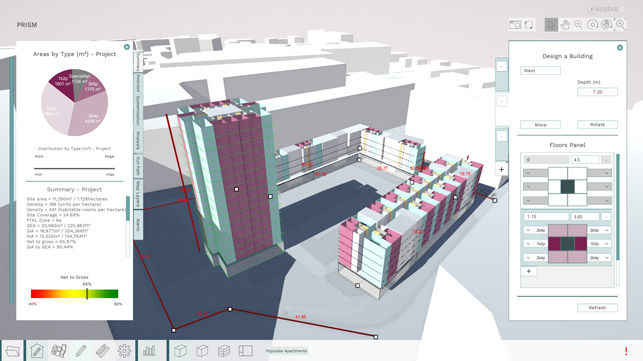

Prism is our open source app to accelerate the design process for precision manufactured housing in London. It’s free, easy to use, and combines spatial planning rules with precision manufacturer expertise to quickly determine viable housing options for a given development. Designs, produced in hours, can then be fed into existing BIM workflows, and in turn into platform-based construction solutions.

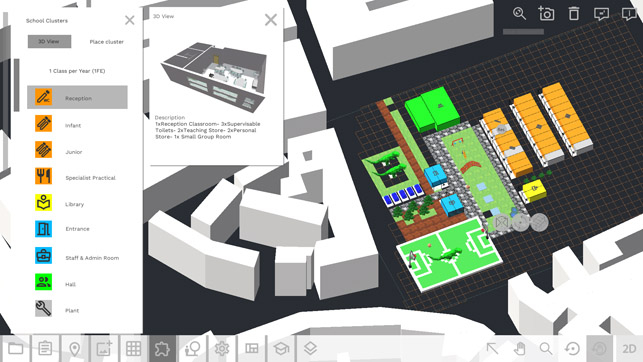

Our Seismic tool accelerates the design of primary schools, this time embedding operational requirements from the Department for Education (DfE) in an app that has successfully been used by children to design their own schools.

For Highways England we developed a rapid engineering model that uses data from an existing asset’s performance to produce 200+ design options as opposed to one option, heavily iterated. The result is a motorway designed in days, not months.

It’s our view that free, web-based apps like Prism and Seismic will remove current barriers to entry, speed up design, and enable many more people to design the buildings and infrastructure we badly need. We’re hoping to create a community who can adapt the apps and boost their functionality. Meanwhile, tools like those we developed for Highways England put new technology directly into the hands of our clients to help them monitor and run their asset as efficiently as possible.

A Platform approach to DfMA

Platforms are sets of components, with designed in compatibility, that combine to produce highly customised structures, highly efficiently. Just as the chassis revolutionised car manufacturing by providing a common platform for customisation, the Platform system is based on repeatable forms and standardised connections, enabling many different kinds of space to be built with a single ‘kit of parts’. In the words of the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA), ‘a single component could be used as part of a school, hospital, prison building or station’.

This point is crucial because sector-specific thinking within the industry has long been a constraint. Many people view housing, for instance, as being separate from and different to anything else, which forces a reliance on demand in one particular market sector. As a result, a manufacturer of a residential system may find it difficult to achieve the full benefits of a manufacturing approach because the housing pipeline is inconsistent.

A universal Platform system, with interoperable components that work across sectors, will allow manufacturers to expand their capability efficiently across building types to be able to service a much larger share of the overall construction market. In turn, creating consistent demand and sustainable pipelines in different sectors.

Interoperability will mean companies don’t have to work in isolation. With Platforms, the industry can work collectively, in a model of continual improvement, to accelerate the pace of change.

Our work on Platform systems has been published, for free, on our website. And, through The Construction Innovation Hub, we have launched an open call for Platform-based solutions to encourage anyone, from within or outside the construction industry, to get involved. This is part of the largest ever Government-backed R&D programme in our sector and closes at the end of this month (constructioninnovationhub. org.uk/platform-design-open-call).

By combining digital design tools with sophisticated DfMA, we can create a new, technology-led process with increasing benefits for all through complete interoperability. Open sourcing both the digital and physical solutions could mean the powerful network effect we have observed in numerous other sectors finally comes to construction.

The skills gap in our sector is well documented and worsening, and understandably Generation Z view a career in construction as bleak and unrewarding. However, a tech-led career in a fast-moving sector creating high performing assets, is a totally different prospect and one we must foster.

What is certain is that open sourcing technology will create a much more diverse workforce across all aspects of the built environment who will challenge and ultimately change the sector.

Although the 1956 judgement was a painful one for Bell Labs, the impact was lasting and positive. The question is, how much more powerful could the outcome for construction be if we voluntarily share solutions, starting now?

It could be the transformative moment we’ve all been waiting for.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our email newsletter or print / PDF magazine for FREE